Git notes

Waffling about mental models, and "For those coming from other versioning systems..."

Asking what and why

As to the what:

Git is a content/source versioning system.

One of many.

A bit more flexible, a bit more complex.

Currently popular.

What do you even use it for?

Why git and not something else? How to choose?

Comparing purposes

Perhaps the largest mental switch is that

- in respository style, you can intuit a commit as "the new revision that everyone should have"

- and global to all users of that repository

- in git's style, a commit basically just identifies an annotated collection of diffs

- which in itself, is local to a copy, not something reflected elsewhere until you make that happen

"in git, everything is local" is meant to say that every copy is an independent, complete, standalone thing.

That's a real difference, but not really the point.

It's a side effect of the distributed graph nature.

It also helps to mention

why was designed this way,

how it is different from other setups,

and when you might want one over another.

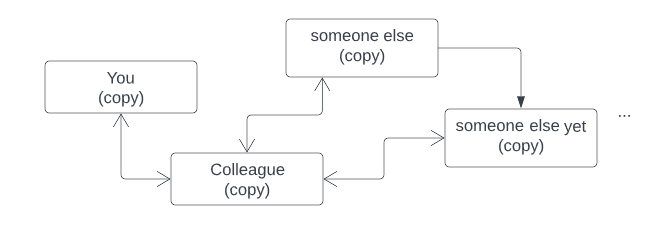

Git is distributed in nature, more specifically a distributed graph, but almost no one uses it quite that way

The main alternative is is diverging from is the central repository, where

- the only place everyone communicates with is that central repository

- the only place where things get committed is that central repository.

- working copies can never diverge much from that repository - the more and longer they do, the harder it is to ever exchange with again

- the concept of "a chunk of changes" is basically "whatever the difference between this version and what it was in the last version"

- the repository is the only thing that tells you how to refer to each revision (which may be a version counter)

- and that's really the only kind of "make changes in the system" operation there is

Git has a different take on all of that:

- that commit is local to your copy - but can be communicated

- every copy can communicate with every other copy (though in most use you still use a central place)

- there is more focus on what content, rather than version (...though there is no hard distinction in the end), any commit is relative to

- as there is no central authority, revisions can't be referred to by version counter

...no one uses it that way.

Most people host on github or gitlab or similar (it seems people shout at you if you don't) - which are repository style setups. The mechanics of exhcange and references are different, but the basic model of exchange mostly isn't, and it is no less likely than others to throw a fit when changes conflict.

But why?

The means of resolving conflicts does not actually vary a lot with the underlying data model, because the problem is generally the same.

And clear communication is typically worth more than the technical part of the solution.

If you communicate often, then a central repository is a fine solution,

and the setup forces you to communicate.

- Even the kernel project has some strong guidelines - and a central repo on github.

Ad hoc use is possible, but just not done, because it's more trouble than it's ever worth.

If people typically work independently, with less or later communication, but still mostly on the same thing, then you need a much better defined idea of "this is the set of changes I want to communicate"

The fact that git thinks more in diffs (and less in "you are working on whatever will be the new version, which we can also see as differences" to whatever the previous central version was) turns out to be more practical for such use.

This also leads to the git's staging -- if you're working on whatever becomes the next revision, then you need not make life more complex than committing that new version to the repo. It'll tell you if and when you need to do some conflict resolution.

But if you need to commit what is essentially a diff, you need to figure out which specific differences you want to transfer. Git makes a point of locally giving a name to a change-set. (This is also roughly why commits are always towards your own copy.)

To be fair, when that's "all changes you've done", there is very little difference.

But the ability to split diffs into more commits also makes code review easier.

This is an important detail for the linux kernel project, because it runs on a benevolent dictator model.

A little more on the waffling side

Relevant snark

- "If the power of Git is sophisticated branching and merging, then its weakness is the complexity of simple tasks."[1]

- 90% of people don't need 70% of git

- and may specifically want to avoid it, because why invite all the extra edge cases - who wants to deal with those?

- ...also, that 30% you'll use is more complex than it is in other systems.

- There are no abstractions, but there sure are a lot of technicalities.

- the CLI should absolutely not be confused for that mental model.

- Say, git reset can do half a dozen different things, in terms of the actual model.

- there is a reason that the CLI is sort of a bad way to learn git - it grew organically and new operations got tacked onto the closest matching command

- Git becomes easier to use once you use third party wrappers instead

- ...of course, each one will have their own workflow, none of which are quite the same

- some of the most useful stuff comes not from core git, but from applications/wrappers written around git, like IDE integration (unless it's bad, then it's worse), or specialized repository interaction software

- that's how easy it is!

- Github has a lot of actually-quite-nice tooling

- ...to deal with things that happen only when you decide to have zero communication with upstream before a lot of code is changed (...that upstream maintainers will typically reject the first version of anyway)

- also, this tooling isn't really part of core git

- more power and flexibility means more edge cases, that you will have to learn sooner or later

- ...usually in crunch time when git throws yet another error you've never seen before

- git can be smarter at handling conflicts than some alternatives

- But when it hits a conflict it doesn't deal with, you better understand git at a deep level. Good luck! (hint: most of us are just pretending, or haven't found this point yet)

- there is a reason github specifically imitates classical repositories

- and considers a linear, squashed history to be 'protection'[2]

- sometimes the best way to resolve errors is to wipe the project and upload a new copy

- unless you're one of the people who actually uses it distributed, in which case - Good luck!

- why does that two-line merge take a minute? Who could tell? Probably your fault though.

- people seem to not tell be able to tell git apart from github

- so we're fine with microsoft feature-controlling even more of our go-to open-source dev environment, then?

- don't use git as backup, because there are several ways you can wipe out contents permanently

- so have your own backup

- incidentally, this is hard to make correct or fast

- git is a classic case of "when these dozen previously things vague snap into place, you will suddenly get a lot of it".

- Until that point you will be actively confused by the fact that you will not be tutorialized, and some concepts are explained poorly and even a bit conflated.

- ...seemingly conflated for the sake of those who already get it to make more concise sentences, at the cost of all learners. (I personally think that was a bit of a mistake, but hey.)

- "Git becomes a lot easier once you understand that [x]"

- ...almost invariably means "I stared at it long enough to internalize enough of it to sort of get it"

- and almost never means "I now produce a statement that will help you understand it more easily", maybe unless you were almost there already (And even if it does, you won't know it from the ones that don't)

- git's documentation seems so adverse to actual explanation that it is nigh impossible to understand unless you already understand git well

- every page one uses terms that it doesn't explain. By the time you've found definitions you've read most of everything and wasted at least one workday.

- Say, git-rebase says it "forward-ports local commits to the updated upstream head".

- Uhhuh, uhhuh.

- That sure didn't say that

- content-wise, it's taking changes on one branch/copy and figuring out what sort of commits you need to do to make the same changes on another branch/copy, and put that in a new commit,

- or the intent is often to cleanly apply such changes elsewhere, e.g. in another copy, or to be able to do your messy dev thing in branches, but still leave the overall main branch stay quite clean and linear

- and that more technically, the point is that your commits are against an earlier version/commit, and rebase allows you to ask "git, please take this later version/commit and figure out the diff/commits against that

- All that may be obvious once you know that, but, um... what is documentation for again?

- This is about as legible

Team contributions versus unsollicited contributions

We generally do not want to play degrees of separation in terms of code -- at best it's a lot of extra steps, extra thinking, and extra typing, and it rarely has an upsides -- we typically still organize with what amounts to a central repo.

Most projects, company or hobbyist, have a vested interest in communicating well, and cooperating tightly.

So we usually avoid the anarchist web structure because when you communicate well anyway it's more trouble than it's worth, and if you don't communicate well it won't save you (and it may make things worse).

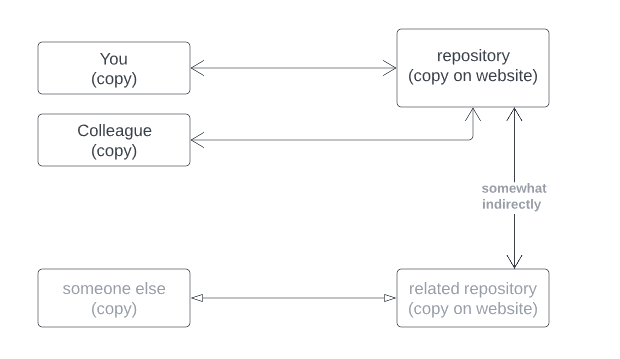

So it turns out that most exchanges are via gitlab/github, or otherwise more like:

(Actually, github suggests history sticking to linear history, a.k.a. requiring contributors to do their own squash merges, or rebase merges. It, in fact, considers this to be protection of the central repository[3])

And yes, you could remove that "somewhat indirectly" part by giving anyone access to your repo, and this is still fully possible with git, and github, and gitlab, and more, and might make sense if you are a small, well defined, fully trusting dev team.

But to get some granularity, particularly in a more decentralized world, we do not trust anyone by default. (Github makes you think about restricting even collaborators from doing pull requests, and considers that protection too[4])

Unsolicited changes were always their own special case, and still are.

Before git, people tended to send you a diff via mail and have the you, the developer, figure it out, an out-of-band thing.

With git, the habit is still "you get to propose a change for the dev to look at".

Yet it's not quite in-band - it turns out this proposing isn't quite a part of git so it's still sort of out of band, except that the tooling is nicer -- yet specific to the hosting (github, gitlab, etc - it's part of why self hosting is not common).

Because github or gitlab have features that help you here. If you don't use those, and aren't Linus, well, it's clunky.

We are describing merge requests, a.k.a. pull requests. In that diagram, this is what that "somewhat indirectly" hints at.

A little more practical

On confusing terminology

Arguably, there is a some not-great naming going on.

It may be easier to understand if you consider (stealing from here), (and a little from here):

- "index" should have been called the "draft snapshot" - its intent would be clearer

- "commits" should have been called something like "(possibly-annotated) snapshot of the whole" (maybe, I'll think about that one)

- though because of the nature of this sort of repository, commit is frequently thought of as "just the subset that is the difference that that makes"

- "branches" should have been called "snapshot lineages".

- "repository" should have been called the "snapshot store".

- "stash" should have been called the "content drafts".

- "working tree" should have been called the "content pool".

History is backwards - on reachability

Communication model

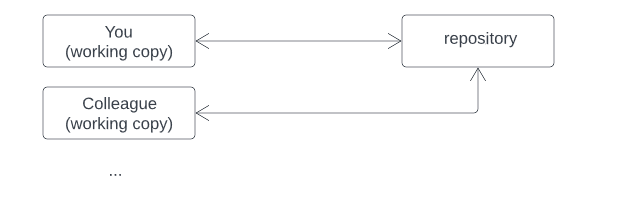

Some people make a point that whereas most other source versioning only talks via a single central place, like:

...git does not require a central place that everything synchronizes with.

You can synchronize commits with one of any configured remote repositories

Also you can pull from and push to different places, and lots more, which would make that diagram even more complex.

What they don't tell you is that we rarely ever do that.

- Ninety percent of the we explicitly all push and pull from the same central repository, so the fact that you don't need to is usually moot.

- And probably ninety percent of that time, that place is specifically called github or gitlab.

Model for your local state

You can think of your own directory you're git-versioning as

- your local git copy, alongside...

- containing file changes you have not yet added to git

- a staging area, so that a commit can be a specific set of changes

- your own HEAD

- your own branches

- and configured relations to other repositories

- You decide

- if and when copies relate/communicate

- which of yor commits to communicate to others

- You decide

- all git repositories are created equally

- there is no repository versus working-copy distinction

- (though things like github imitate this)

- also meaning all copies have a complete revision history

- Commits

- think of them not as "the new revision that everyone should have" (as in repo/working copy), but of each commit as a specific annotated collection of differences

- a commit is local unless communicated

- each commit has an id

- each will chain onto a previous commit

- which a lot of the time makes a straight line (one parent) but occasionally branches (two things have the same parent), and merges (multiple parents)

- (the structure is a directed acyclic graph)

- you stage a bunch of changes, then commit that to your own copy (in a single transaction)

- the index is what you stage to, which you build up interactively

- So you generally have to consider HEAD, the index, and your working directory, and also the stash if you use it

- The previous point is why some commands have more modes than you'ld think

- as an example, git reset can be used to

- remove things from being staged

- remove a last commit from HEAD, but don't touch your files or what is staged

- remove a last commit from HEAD, and clear what is staged, but don't touch your files

- restore working directory to HEAD, losing all local changes

- restore working directory to HEAD, except if you have uncommitted changes

- ...which are wildly different things, all of them useful, but you need a presentation or a long think before you understand how exactly

- if you want to communicate such changes between copies, you need to

- tell git how copies relate

- explicitly trigger what to communicate

- You can use git much more decentralized if you want, but the "we use this one spot as a repository" is common because it's easier for most uses

- in which case:

- git clone will usually make it relate to where you cloned it from

- after which you can git pull and git push.

Stuff you should learn better eventually

Branching

Merging

Introduction by example

Client setup (optional)

Note: You may wish to set how you'll be identified elsewhere: (...actually saved in your ~/.gitconfig)

git config --global user.name "My Name" git config --global user.email my.name@example.com

There's some other config you may want to play with, like:

git config --global color.ui true

Starting to work with versioned code

Perhaps the simplest way to start is to

- create (or find) a project on github, and

- clone it

- implicitly sets up that project as the origin, e.g. for later pulls (and, if it's yours, also pushes)

git clone https://github.com/example/test.git

For some local tests, you could create a completely blank repository

- good for messing around, but you e.g. won't get to test any pushing or pulling until you learn how to set up origins and such.

git init

Also keep in mind that if you make a copy of a git directory (including its .git metatada), you get a separate copy you can play around with.

(This is also the simple-and-stupid way to make backups)

Basic staging and commits

Undoing things

See a few commands in the conflict resolution below

Inspecting local state (staged, committed but not pushed, stashed)

Inspecting some stuff

Communication

Interacting with connected repos

Pull requests basically mean you saying "hey collaborator, I've completed adding this feature to your code, might you want to integrate it?".

Pull requests aren't really a git concept, they're added by git hosters.

And they make more sense to do with such a more centralized place, than with a "everyone has their own copy" variant, if only because of the amount of confusion involved.

Branches and communication

Tags

On using someone's existing branches

Pull requests / Merge requests

Branching for cooperation

- shared branches

Conflict handling

Specifying commits and ranges

Undoing things

Resolving conflicts (also: undoing things)

stashing

More regular

"Your local changes to the following files would be overwritten by merge"

You have changed a file. (which is a difference to remote copy)

So did someone else. (which is pushed into that remote HEAD)

You are pulling their changes.

That pull (which is fetch + merge) wants to update a file.

A file you have changed - so that's a conflict, in that you probably don't want it to overwrite what you have done.

"Updates were rejected because the remote contains work that you do not have locally"

Your branch is behind 'origin/master' by 8 commits, and can be fast-forwarded

error: You have not concluded your merge (MERGE_HEAD exists)

The previous pull needed to merge, tried to merge, and failed to do so.

There are multiple reasons you can get into that situation, and the best fix will vary along.

Your configuration specifies to merge with the ref 'refs/heads/master' from the remote, but no such ref was fetched

Seems to mean that that ref doesn't exist - anymore, or never did.

Chances are this came from a git pull, which you'll remember is effectively a git fetch plus git merge,

and it is the latter that complains.

(not that a git merge gives the same error, but hey...)

Other messages and errors

fatal: detected dubious ownership in repository

Some files are owned by other users, e.g. root, which is potentially security-relevant. (That is, if you share storage with untrusted users, them editing your .git/ can be Bad)

Apparently it won't tell you what it saw, though.

Which is probably why the suggested fix is "no just trust it, and ignore this security warning", but it's probably a good idea to actually look at the ownership first.

Options

- change ownership, often something like

chown username:groupname /path/to/dir -R

- say you don't care

git config --global --add safe.directory /path/to/dir

You are in detached HEAD state (and: what is HEAD)

This repository moved. Please use the new location

This is github informally telling you that the repo was probably renamed, it's resolving that for you, but you may want to change what you're referring to.

You probably want to do:

git remote set-url origin 'new_url'

Altering history (and potentially creating bigger problems)

Credential stuff

Credential management

github personal access tokens

A few years ago, github stopped allowing passwords in credentials.

It wants you to use access tokens, which are a mix of

- a longer password

- each (yourusername,atoken) pair

- can be associated with its own rights

- can have its own expiry

As https://docs.github.com/en/authentication/keeping-your-account-and-data-secure/managing-your-personal-access-tokens explains, generating a token is done at:

Settings → Developer settings → Personal Access Tokens → Fine-grained tokens

Criticism #1: this is coarse grained, mostly allowing "write to all my repos"

Criticism #2: It does not explain how to actually use it.

- sort of makes sense, in that each client does it its own way -- including how it prefers to store the credentials

- but some instructions for common clients would have been nice

Semi-sorted

Backup

Git URLs

What's with pull requests?

fast forwarding

degit

Looks to me as if

degit some-user/some-repo

is functionally much like

git clone --depth 1 https://github.com/some-user/some-repo && rm -rf ./some-repo/.git/

It mostly seems used by webdevs who put a template on github, and want to save keystrokes fetching it and leaving no extra mess.

Notes:

- actually does more, e.g. fetches a tgz into a cache in your user dir, which speeds up repeat installs

Unsorted

See also: (TODO: do so myself)

Reference-like:

Introductions:

- http://marklodato.github.com/visual-git-guide/

- http://scottr.org/presentations/git-in-5-minutes/

- http://www.gitcasts.com/

- https://git.wiki.kernel.org/index.php/GitFaq

- http://progit.org/book/

Discussions and other:

git GUIs

In no particular order:

- gitkraken (win+lin+osx)

- git-cola (win+lin+osx)

- smartgit (java)

- gitg (lin)

- comes with git:

- git gui (more for management, not so polished)

- gitk (mostly a viewer)

- qGit (mostly a viewer)

- giggle (mostly a viewer)

...also note that various IDEs have integrated git. Some of them are quite good, even, and potentially more convenient than anything external.

github-specific

Extensions to git

Pull requests

LFS

Hosters don't like you pushing large files.

Nor will you, when

- you realize that changing large files will mean the bulk of space taken by all copies is now versions of that file.

Remember, one of the selling points is that everyone has a full version history (yes, you can actually remove things from that history(verify), but it's not really intended).

- you notice git would taking minutes to do anything, and trashes your computer when you try a gc or repack.

So e.g. github warns you above 50MB, and refuses above 100MB, and limits your repository to a few GB.

Other hosters have similar limits.

Git LFS (Large File Storage) is an extension developed and used by some of these git hosting sites.

It comes down roughly to

- your repository stores what amounts to a pointer - to a completely separated storage (that we happen to call LFS)

- specific clients know what to do with that

For that to work, in a regular add/commit/clone/pull workflow, all collaborating clients (and probably the git hoster) need to support this LFS extension.

- A client with LFS support will work transparent in that it will fetch the content that this pointer points to

- A client without LFS support installed will just see files that happen to contain these pointers)

The specific service called LFS has a (rather opaque) set of limits to storage and to bandwidth[5].

- so beware - using this for actively changing data is effectively a paid service

github specific

"Your main branch isn't protected"

gitlab specific

groups

https://docs.gitlab.com/ee/user/group/

Merge requests

Basically the same as pull requests