Color notes - the eyes and the brain

The eyes

SPDs may have scientific uses, to do reproduction not just for human eyes, and to keep the underlying mechanics in mind.

...but for many practical uses for consumption of human vision, it helps to know what the eyes do to flatten/simplify this.

In this context the retina is most interesting.

The retina is the back of the eye, the bit that's actually sensing the light,

with rods to sense just intensity, and cones to sense colors.

The reception of cones' is called 'tri-stimulus', meaning they describe what they see in terms of the intensity of three signals - three colors.

At a physical level, cones are basically a colored filter in front in the form of a pigment, before the light that's then left over gets to the light-receptive area.

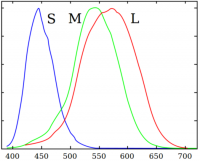

There are effectively three types of cones, responsive to three different (and overlapping) ranges of wavelengths.

Quite usually this is referred to as L, M and S refer to longer, medium or shorter wavelengths (relative to each other).

Their peak sensitivity (approximately 610, 540 and 420nm, respectively) roughly corresponds to with red, green and blue, but this is somewhat misleading, because these response curves both overlap considerably, and have different shapes.

Rods have no pigmentation filter so receive only brightness information.

Their response peak is around ~520nm, putting it between S and M at a slightly bluish green.

Rod, cone, and cone type distribution; sensitivities; night vision

Rods versus cones

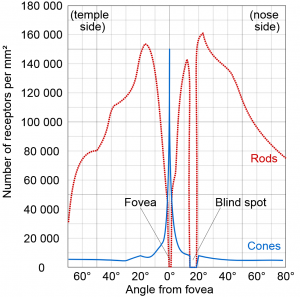

From the center of your retina (the fovea)

- from zero to about two degrees: many more cones than rods

- meaning we see color best in the center of our vision.

- about two to 15°: more rods than cones

- beyond 15°: mostly rods

- meaning our peripheral vision is more light-sensitive, and explains the ability to see things slightly better in the dark by not looking at them directly.

Apparently rods also resolve a little less detail, as cones connect to a single signal nerve but rods usually have to share a little.

Cones versus cones

In general, you have more red cones than green cones, and noticably fewer blue cones (~2%?). So we see red a little faster and a little more accurately.

For blue, we are similarly sensitive to its intensity, but with fewer cones, we essentially have lower resolution so find it harder to see detail in it.

General notes on sensitivity

Sensitivity and discenrability varies with light levels, because of how cones or rods respond. The technical terms:

- Photopic vision: refers to vision under well-lit conditions, primarily with cones (1 to 1000000 cd/m^2)

- Mesopic vision: darkish vision at which you have limited color vision(at about .02 to 1 cd/m^2)

- Scotopic vision: refers to the monochromatic vision in low light, when cones do not work (about .02 down to about 0.000001 cd/m^2)

On night vision

Warning: Popular fact is regularly myth here, and I'm not sure all this is right.

Night vision is mostly due to rods.

Since the center of our vision has a low amount of rods, relatively speaking there is a nigh vision blind spot in the center few degrees of our vision, and our peripheral vision is actually better at seeing things in the dark, though it isn't very easy to use that.

Night vision being usable depends on the amount of rhodopsins in your eyes, and its regeneration. rhodopsin depletes in daylight-level intensities.

When it regenerates, your eyes can do more with the same amount of light.

A few minutes is enough for regeneration of one or two dozen percent (at which point you start noticing night vision), fifteen minutes for the bulk of it, and over half an hour for almost all.

If you want to illuminate something in the dark -- instrumentation, a dark room, or such, the best color to use depends on 'what for'.

The main choice here is:

- do you want to see detail

- or do you want the least effect on your night vision?

These are at odds almost by definition, because that which makes us see better also depletes rhodopsin. But it's a little more complex than that.

When you value night vision above all, then higher-frequency reds gives slower depletion of rhodopsin in rods and the night vision it provides, than blue, green, and lower-frequency reds give.

If you care more about detail (than about minimal effect on night vision), for example for quick-glance readability of relatively precise instrumentation, then various colors will do, and arguably (dim) white is better.

Also, you may care a to use the center of your eyes to read out these details - which primarily has cones.

You can argue that any color will do, and red slightly better as you have more red cones than other cones. However, rods respond to lowish red frequencies, and (aside from depleting night vision a little) that means your brain will get a signal from both rods and cones. In near-darkness (up to lowish mesopic), both signals are noticable, and your brain having to interpret the combination is less readable(verify) (and perhaps a little more tiring).

Higher-frequency reds are useful in that you get more response from cones than rods that way(verify)

See also

Color blindness

Pretty much all possible malfunctions that intro makes you think of can happen, but of all of those, only one or two are common.

There are also two main ways to categorize the common types:

- by their causes (e.g. low cone response),

- and by the effect they have (which colors are harder to distinguish).

The former is more precise, the latter more pragmatic/easier.

Note that not distinguishing colors as much is the only real effect - people don't randomly see different colors. They may be able to focus more on brightness difference because of it(verify).

Unusual (often meaning limited(verify)) response to one type of cone is one common type of problem.

Because of the opposite-processing of transmission, both protanomaly (proto referring to L cones) and deuteranomaly (referring to M cones) limit the red-green channel, while tritanomaly (S cones) limits blue-yellow.

Missing response of the L, M, or S cones is called Protonopia, deuteronopia and tritanopia respectively, and means little response on one of the opposite-processing channels.

Deuteranomaly (implying red-green) is most common, affecting 5% of men, while the rest affects 1% or less of anyone.

The anomalies are hereditary, in mildly complex ways.

There are other ways of damaging your eyes, but since it's selective, this is a little harder.

See also:

Related:

Nerves and the brain

Color mixing and opposite processing

It was observed by various people that we don't see certain colors mixing. While 'greenish blue' and 'yellowish red' work as descriptors because we can imagine what that mixes to, 'greenish purple' or 'blueish yellow' doen't.

This non-mixing isn't so much an effect of reception, not part of the cones, but instead caused by the way their signals are processed before they are sent to our brain.

Before sending signals to the brain, our eyes convert to a system named opponent processing, that turns the three types of cones' signals into two channels.

Essentially, one channel is red stimulus minus green stimulus, the other yellow minus blue. Note there are no yellow cones; yellow comes from the combination of L and M (red and green) cones. In reality, effects like the overlap of conce response make this even more complex than described here -- get a good book if interested.

(It also helps explains the two typical types of color blindness - if one of the types of cone pigment is missing, one of the described color signals has little or no range)

After processing, less signal on the red-green means you see green, more signal means you see red. Little on yellow-blue means yellow, more means blue. (See e.g. this for a graphic explanation and this for a textual one)

Sensing both colors on a channel at once is neurally impossible, making the eye a bad tool for measuring the spectrum. This signaling is one of the main reasons for metameters, non-identical spectra (SPD's) which we see as the same color, (depending also on the environment light - which is a problem, as color differentiation is different under different light sources). The existance of metameters sounds like a problem, but without them we would have needed a lot more color names and crayons in a kit - pretty much one for every noticably different SPD.

The fact that the neurons and the mind adapt in short and long terms is the reason for effects like

- after-images of signals that oppose according to the opposite processing model (stare at red and you see greener for a few seconds, see eg. this example),

- slowly adapting night vision, as the rods take over from the cones - also why we're mostly colorblind in the dark,

...and a few more complex effects.